Emerging Victorious

It’s been a year. For 13 months, Brown students were isolated, masked, and tested both literally and figuratively. Each one of them performed exceptionally, making it through COVID with determination and resilience, but we can’t fit 2,505 stories into this 10-page feature. So we’re focusing on just seven of the countless exemplary students who earned bachelor’s and advanced degrees this year. Despite having a final year at brown so challenging that it’s literally one for the history books, they’ve created, achieved, and helped others. Thanks to the pandemic, those able to exit may 2 through the Van Wickle gates in person had no families or alums applauding their achievement. These pages will have to serve as our applause—and we ask you to imagine, as you read, the hundreds of other students whose stories remain untold, and send them all a silent cheer.

HEALTHCARE ACCESS

Melanie Anaya

Long ago, while still an elementary school student, Melanie Anaya ’21, ’25 MD, helped her mother study for and pass her citizenship test. Anaya now teaches her own citizenship class through the Providence Public Library for Rhode Island immigrants.

A first-generation American and student in Brown’s eight-year Program in Liberal Medical Education (PLME), Anaya appreciates how important citizenship is to accessing better health care. And she’s been thinking about how doctors can better reach underserved communities for years, prompted by annual visits to her mother’s rural hometown in the Mexican state of Michoacán.

“For people there, it’s really hard to get the help they need,” Anaya says. “It shaped the way I wanted to practice medicine—to go to the community instead of waiting for people in the community to come to me, as a physician.”

Anaya concentrated in Latin and Caribbean Studies and Hispanic Studies, focusing on the communities she plans to work with in the future. “The humanities foster empathy, understanding, and curiosity to learn more about a person,” she says, “and that, I think, is really important when you want to know a patient.”

In the months before the pandemic, Anaya studied in Cuba, coming away impressed with the community-oriented, preventative nature of its renowned healthcare system. For her capstone project, she researched the disparities in health among Indigenous communities in Mexico following the early 20th century Mexican Revolution and the consolidation of a national healthcare system at the expense of traditional cultural practices.

She’s also coordinated Latinx Heritage events for the Brown Center for Students of Color, guided incoming PLMEs as a Meiklejohn Fellow, and worked as a teaching assistant for public health and Spanish language classes. But she says she often felt lost: “Neither one of my parents even graduated high school, so they couldn’t help me in college, much less in medical school.” As a second year, Anaya cofounded the First-Generation/Underrepresented in Medicine (FURM) Committee, which helps students navigate preparations for medical school with an emphasis on diversity and inclusion, one goal being to bring in more speakers and patients of color to interact with students and share their experiences in the healthcare system.

During Anaya’s internships at the BronxCare Health System and Rhode Island Free Clinic, she saw firsthand how cultural and linguistic barriers could hamper patient-doctor interactions. She served as a Spanish language interpreter at the clinic, relishing the moments when she could chat with clients as people. “Advocating for the patient is really important,” she says, “especially when there is this language barrier, because language is such an important thing with so much nuance. It made me realize how important it is for me to become a physician.”—Ivy Scott ’21.5

FOOD SUPPLIED

Aidan Reilly

Shortly after COVID hit last year, Aidan Reilly ’21, an international relations and comparative politics major, was back home in L.A., feeling not only bored but helpless to do anything about COVID’s toll on the country. Almost simultaneously, he learned that farmers nationwide were throwing away tons of food because the pandemic had broken down supply chains—and that the Westside Food Bank, where he’d volunteered as a kid, was suddenly struggling to serve 1,300 families instead of the usual 300.

“I wondered if maybe these were two problems that could solve each other,” he says. Enlisting help from his friends James Kanoff and Will Collier ’20, he started cold-calling Southern California farms, asking who had extra food, until he found someone who didn’t hang up on him. Next thing he knew, he was driving a rented U-Haul with 12,000 eggs in it to the Santa Monica food bank.

That’s how the Farmlink Project was born. Slightly more than a year later, run by Reilly and staffed by college-age volunteers, it has delivered 30 million pounds of surplus food to food banks and similar centers in 48 states. It’s also raised more than $1 million in direct relief to farmers.

Reilly had no idea such a project would end up the centerpiece of his senior year. “On April 1 of last year,” he says, “living back at my mom’s and coming out of a breakup, I wrote myself a note saying to set myself a goal for ten months from that day. And so many aspects of that goal have come true through Farmlink.”

“I’m thinking in terms of families who have to wait in six-hour lines for a bag of food. That’s something I’ve never had to do.”

Not that he was slouching earlier in his career at Brown. In addition to being a star player on the Brown water polo team (in fact, it was assistant coach JJ Addison who nominated him to be in this issue), he’d already made two documentaries. One of them, Asma, about an 11-year-old Syrian refugee girl in the Beqaa region of Lebanon, played in several documentary film festivals. “My mom’s a documentary maker, so I grew up watching tons of them and filming stuff,” he says.

But all that’s changed, at least for now. He intends to continue working on Farmlink full-time from L.A. for the indefinite future. He’s transitioning the project from volunteer to professional truck drivers and just hired its first paid staff. He hopes to find ways to weave documentary filmmaking into his future, but right now there’s no time for thinking about anything but the issues the nonprofit has started to tackle. “Twenty billion pounds of farm food get dumped every year, even without COVID,” he says. “Going from being a pretty solitary person to a leader of sorts has demanded a lot of growth from me. But I’m thinking about this in terms of families who have to wait in six-hour lines for a bag of food. That’s something I’ve never had to do.”—Tim Murphy ’91

MUSIC LAW

Xiaoyu Huang

Calamity struck the Brown Orchestra on the eve of a concert in 2019, when its pianist dropped out before a performance of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony. Someone needed to step up, but they would have to play with almost no preparation, and Prokofiev isn’t exactly “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.”

The Orchestra knew just whom to call: Xiaoyu Huang ’21, a pianist who can play complicated music on sight. “That was probably my favorite music moment out of my entire life,” Huang recalls. “To have to play it without the security of having practiced it... You’re ultra aware of what’s going on, the high stakes.”

Hired by the University as a pianist to accompany student musicians—who are often pursuing a career in music—Huang was entrusted with supporting them at concerto competitions and auditions, a rare responsibility for an undergraduate (most institutions have a professional fill the position). He once played in 10 half-hour competitive performances back to back.

Before becoming music director of the Chamber Orchestra this year, Huang labored for years as an assistant conductor, a sort of musical understudy role that required him to be mentally prepared to lead the orchestra, memorizing all the music and understanding the role of every instrument.

Equally adept at dealing with logistics and with a voracious appetite for getting things done, Huang served as the chief operating officer of the nearly 200-member Brown Political Review and as the full-time, paid vice president of Pansophy Education Institute, a tutoring and immigration services organization he cofounded in his hometown of Vancouver. A passionate educator, he also served as a teaching assistant in numerous classes. He’s been an “enthusiastic and integral” part of the musical life of campus, says Mark Seto, director of Brown’s orchestra and the music department’s undergraduate studies director.

Though he had initially planned to develop and conduct his own concert as a thesis, the pandemic forced Huang to rethink. A triple-concentrator in Music, English, and Public Policy, Huang pivoted to tackle the dense topic of music copyright law, arguing in his thesis for a more inclusive view of music ownership after scrutinizing an array of complex legal cases and the esoteric laws used to adjudicate them.

Huang “demonstrated this wonderful ability to synthesize this literature of deeply technical legal stuff with an immense knowledge of music,” says Seto, Huang’s thesis advisor. “It was a thesis that could only be written with those two skill sets.”

And Huang’s not stopping there. Current law “really limits the music industry to a few big players who can afford to fight these really protracted legal battles, which I find to be quite disturbing,” he says. After finding inspiration serving as a citizenship and immigration intern for Dorcas International Institute of Rhode Island, he’s now pivoting once more: he plans to attend law school focusing on commercial litigation, with an eye toward internships at law firms that help refugees resettle in Rhode Island.—Jack Brook ’19

HARDCORE BIOMED

Bianca Brown

Bianca Brown ScM ’21 PhD ’21 has never actually seen the blind spiny eel—and of course, Mastacembelus brichardi has never seen her, either. Nevertheless, she’s intimately acquainted with the creature after two years at CUNY York studying its speciation as a result of the unusually turbulent rapids that stir its home in the Congo River.

“I’ve never been to the Congo, I’ve never gotten to touch them; I learned about them through videos and pictures and test tubes,” explains Brown, who first came to the U.S. from Jamaica as an undergrad intending to study pharmaceutical science until her first-year CUNY biology professor roped her into joining her molecular ecology lab.

“It forced me to think about building collaborations and how far-reaching your research can be, even if you’re stuck in a particular location,” adds Brown, whose first paper was published in 2015 just after graduation and whose findings reside at the American Museum of Natural History. “It was a really eye-opening international view of science, and it really set the bar high.”

Little wonder, then, that her next step would be stretching the limits of Brown’s ecology lab to tackle a PhD in the cutting-edge field of metagenomics—the study of all the genetic material recovered from various organisms in an environmental sample, rather than the genes of just one organism. Focusing on the gut microbiomes of wild animals in Kenya—not captive animals, whose microbiomes tend to be different—she completed her dissertation in four years. “In our field that usually takes five or six,” says Tyler Kartzinel, head of the conservation biology and molecular ecology lab that Brown joined in 2017. “I don’t know anyone else who could or would do that,” he adds, “but that’s just who she is.”

“It forced me to think about building collaborations and how far-reaching your research can be, even if you’re stuck in a particular location.”

In addition to being the first student ever to join Kartzinel’s lab, Brown has made history as the first Black person to graduate from Brown with a PhD in ecology and evolutionary biology since the department recruited its first grad student in 1983. She has served on countless diversity committees, been asked to consult with the R.I. Department of Environmental Management, and is frequently a fan favorite at conferences thanks to the vivid illustrations that accompany her research—a product of her partnership with RISD students to merge STEM fields with the arts.

Brown’s next stop is a post-doctoral fellowship in a disease ecology lab at Yale. “We’re all living through a pandemic, and so even though I can’t predict the outcome of her research, I know it’s going to make a difference in ways that the whole world is realizing matter right now,” says Kartzinel. Brown is gifted at tying together research from different disciplines, he adds: “It’s really hardcore biomedicine. It’s always got an eye towards environment and society, and then there’s the creative, human element. All good lists come in three, and so maybe that’s the three-legged stool that best describes Bianca and why she’s so successful.”—I.S.

POLICY POWER

Sonya Brooks

About a decade ago, raising three kids as a single mom in Oakland, California, Sonya Brooks ’21 AM had her aha moment about the structural racism in education that holds back Black and brown students. Her elementary age son, Chase, was assaulted at school by a white student, she recounts—but it was Chase who was suspended. “That,” she says, “left a really bitter taste in my mouth.”

Once her kids were fully grown, after periods of homelessness and sticking out a job she hated in order to support her family, she resumed her undergraduate studies at UCLA in 2018. She began to learn about the school-to-prison pipeline that often sends low-income students of color into the criminal justice system rather than on to success. “I started seeing how the challenges my own children faced at school were reflected in the broader system,” she says.

She was determined to continue her education so that she could play a role in creating policy that would empower Black and brown young people. This May, she received her master’s from Brown’s Urban Education Policy program. COVID has forced her to study largely via Zoom from Oakland, focused on research that centers young people’s reservoirs of excellence and resiliency rather than their deficits and pathologies, as white-driven research into so-called “urban education” has often done.

“I started seeing how the challenges my own children faced at school were reflected in the broader system.”

She has paired those studies with an internship in the Oakland school district, where she is a full-time counselor. In that role, she trains educators to recognize implicit bias and microaggressions toward students as one pathway toward pedagogic equity. She also started an area support group called Beautiful Brown Girls. “We talk about being girls in spaces that don’t normally allow us to show off our excellence,” she says. “I tell them, ‘God gives us all a test—but if we fail, he gives us a make-up test.’”

Brooks, who was chosen to speak at Brown’s graduate commencement ceremony, will now work toward her PhD and law degree at UCLA, with a focus on the intersection between urban policy and the law. She wants to teach high school and college students and eventually become U.S. Secretary of Education. “Because of everything I’ve gone through, I want to fight for parents, students, and communities that don’t have the wherewithal,” she says. “And by that, I mean fight for good policy.”

It was Chase who nominated his mother to appear in BAM. “She literally put her life on hold to raise my two sisters and me,” he wrote. “She tends to go unnoticed, so I wanted to take this time to let you know about this wonderful woman who always thinks of others before herself.”—T.M.

TV TALENT

Amelia Spalter

When her dad fell asleep in front of the TV, Amelia Spalter ’21 kept watching. “I was watching Seinfeld in utero,” Spalter quips. “I always got the jokes—and to the peril of my kindergarten class, I was always repeating them.”

Spalter became obsessed with television and its cultural power, ditching traditional high school to focus on screenwriting while taking film classes at nearby NYU and getting her GED on the side. Finding film school too vocational, she immersed herself in Brown’s Religious Studies department, and soon became fascinated with how deeply embedded religion is in our social fabric—whether we’re aware of it or not.

“Religion is really working us with puppet strings and I want to understand why,” says Spalter, who led the department undergraduate group, planning events and discussions.

Spalter’s inspiration to explore religion through television occurred while attending a talk by survivors of the 1993 Waco tragedy, in which dozens died after federal agents surrounded the compound of the obscure Branch Davidian religious group. The survivors described how sensationalist media coverage only deepened their trauma, but the nuanced 2018 miniseries Waco had allowed them to reclaim the narrative. Spalter later interviewed them extensively for her honors thesis, which investigated how fictional TV shows can promote religious literacy. (One key, she suggests, is treating religion less as a singular, sensational “event” in the plotline and more as an aspect of life unfolding in the background.)

People with seemingly polar opposite views often have much in common—an insight she plans to leverage to make stories that can bring people together.

Her other activities include developing a pilot for a dramedy called Modern Day Saints about a sheltered, devout Mormon who leaves Utah to play lacrosse at an elite New England college, culture shock ensuing; and leading a screenwriting workshop for Brown and RISD students. She also cultivated a talent for interviewing famous and interesting people, both for the Brown Political Review and for a publication she founded, Brown University Interviews. She’s pulled off wide-ranging conversations with everyone from Black Lives Matter cofounder Patrisse Cullors to the lawyer Alan Dershowitz. She says getting celebrities to engage with “some random undergraduate they’ve never heard of’’ is rarely easy. But Spalter is relentless, and found ways to pierce their PR defenses to convince them she was worth their time. The interviews helped her appreciate how people with seemingly polar opposite views often have much in common—an insight she plans to leverage to make stories that can bring people together.

“That realization is one of the most important things I’ll take away with me from college,’ says Spalter, who gave a TEDx Talk on the subject.

Next she’ll pursue a master’s in religious studies at Brown, then business school—steps toward becoming a TV industry leader. “I’m going to start a production company,” she says. “I want to not only make my own scripts, but create an avenue for other people who would otherwise not see a direct path to screenwriting to get their own scripts made.”—J.B.

EDUCATION EQUITY

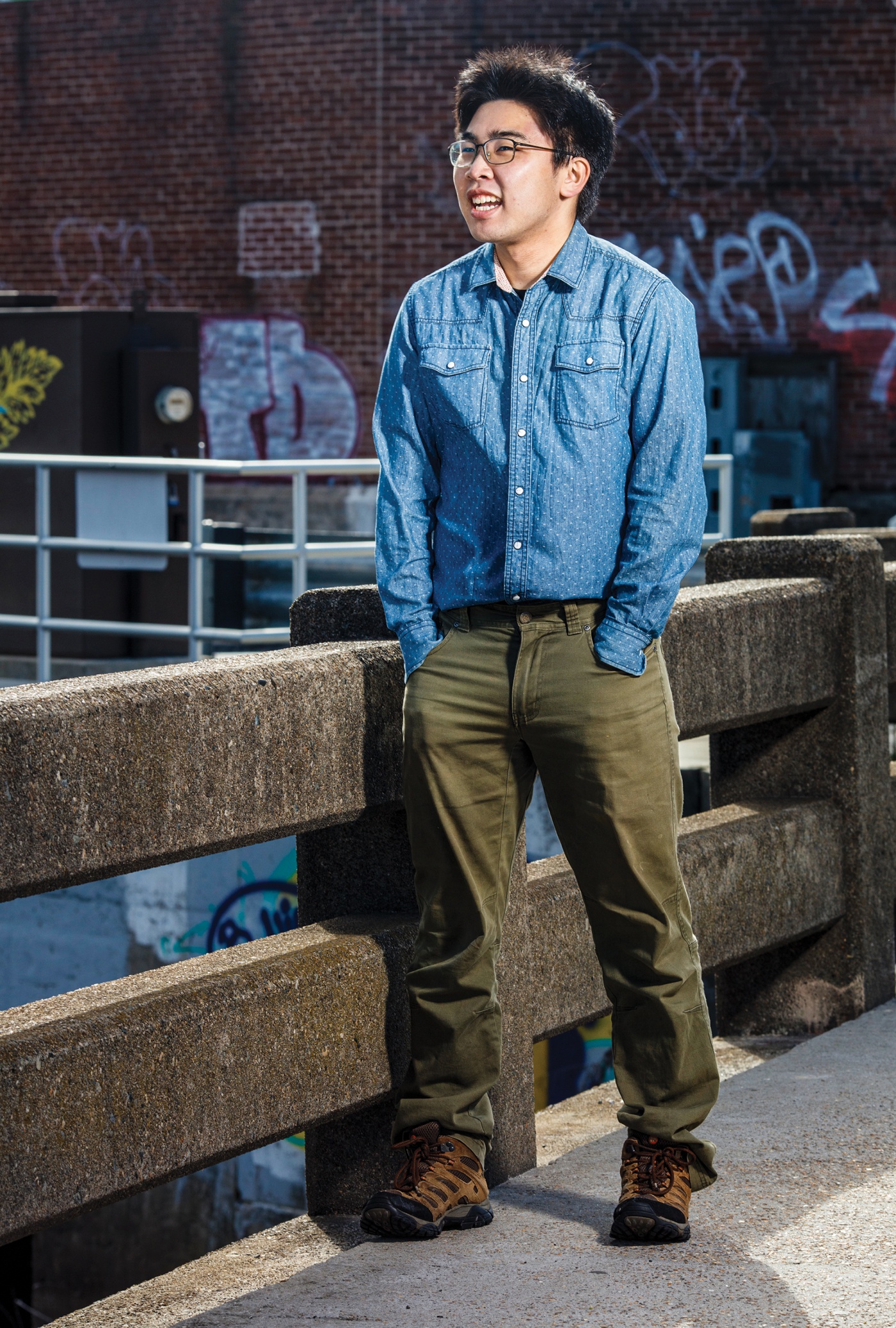

Nari Kato

Growing up in a culturally diverse part of Torrance, California, speaking Japanese with his parents, Naotaro “Nari” Kato ’21 noticed that high schools in richer, whiter parts of the community would send far more students to Ivy League schools than his own did. “People would say to me, ‘You deserve to go to a better school,’ which made me upset,” he says. “I think my high school was very good, but still I questioned how communities only miles apart could be so different.”

That sparked his desire to become a teacher “in order to help close that gap,” says Kato, who earned his bachelor’s in education studies this year and will stay at Brown to pursue a master’s in teaching math next year. “Many teachers helped me get to where I am. Activism and policy and reform are valid, but I’m interested in the role of teaching to create social equity.”

It’s something he’s thrown himself into at Brown “tirelessly,” according to a praise-filled statement from Brown President Christina H. Paxson that celebrated Kato winning a Newman Civic Fellows Award. In his role as a Bonner Community Fellow at the Swearer Center, Kato has spent more than 1,000 hours teaching English to 100 adult language learners at two local organizations, English for Action and English to Speakers of Other Language (ESOL). “I felt like I was supporting adults just like my parents, so it didn’t feel super new to me,” he says of his learners.

His teaching style doesn’t include rote recitations of conjugations. “We ask them what they want to learn and respond to those needs, creating a lesson plan from scratch,” he says. “So if someone wants to learn more about communicating at the supermarket, we’ll focus on that.” He starts by teaching learners how to say “I like...”, “I need...” and “I want…”

As Paxson’s statement points out, there’s nothing one-directional about Kato’s teaching style. “I’ve learned more from my learners than I’ve been able to teach,” he says. “They bring in stories that are funny, adventurous, heartbreaking.” One learner told him about getting to the U.S. via “La Bestia,” the notoriously dangerous freight trains that desperate Central American migrants board to carry them across Mexico to the U.S. border.

When COVID pushed Brown students from campus last year, Kato created about two dozen short, funny instructional videos on YouTube that he sent to his learners via WhatsApp. “But they circulated beyond my learners,” he says, “which made me think about how to use tech to teach ESOL to a bigger audience.”

Once he begins his MAT next year, he’ll be teaching math at a Providence or Central Falls high school. After that? “I definitely want to keep teaching at least a few years in Rhode Island, because people here have been extremely compassionate to me and I want to pay back,” he says. After that, he’s headed back home to Torrance to keep teaching.—T. M.